Evidence of Learned Look-Ahead

TL;DRDive into how Leela Chess Zero, a class of neural networks to play chess, implements planning through a look-ahead mechanism. We’ll break down the key findings of the linked article and explore the interpretability techniques used to study the model, like probing and activation patching. These findings will be reproduced using the library

lczerolens, a tool for chess XAI.

AcknowledgementI want to thank Imene for reviewing an advanced draft of this post and providing useful feedback.

Side NoteThis post will explore the findings in @1 (“Evidence of Learned Look-Ahead in a Chess-Playing Neural Network”) and port them to my chess XAI library

lczerolens. The main goal will be to make it easy to extend the experiments of the article with different XAI methods or on different models, nonetheless I encourage any interested reader to have a close look at the article and their code available here.

# Leela Chess Zero

Chess-Playing Agents

Leela Chess Zero (lc0) is a neural network-powered chess engine trained via reinforcement learning and self-play @2. Originally it was an open source reproduction of the groundebreaking algorithm AlphaZero @3, but since the launch of this project the Leela team pushed many improvements like the latest transformer series of models @4. At the heart of the lc0 chess engine there are two main components, the neural network, which can be modelled has an advanced search heuristic, and the Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS), which is a brute force operator that simulates game trajectories in order to find the best strategy.

The experiments from the article are only meant to study the network part, leaving the MCTS aside. Indeed, trying to interpret the MCTS along with the network can be harder, but understanding the standalone complex heuristic is already an interesting challenge. This network takes in input the board squares as tokens, process them in a Transformer architecture and then produces three outputs through the policy head, the value head and the move-left head. In practice these outputs then serve as a complex heuristic that guides the MCTS by a smart initialisation on new nodes.

DisclaimerI won’t enter much more in the details of the chess engine nor the training process. I’ll refer the interested reader to look at the additional linked resources.

Model Architectures

One of the underrated artifacts produced by the Leela team is the astonishing number of different networks. They trained models with various architectures, number of layers, hidden sizes, number of attention heads; and they provide a ton of training checkpoints. This makes it one of the best interpretability testbed project, a true drosophila for XAI researcher.

Future TrackA possible future track, IMO very interesting, would be to do a thorough benchmark study across the various trained models. Comparing the features learned with respect to the training time and the model size might yield valuable insights, singular learning theory could prove very handy here.

CNN-Based models were originally chosen for chess for AlphaZero and lc0 as they were proven efficient to deal with the structured data of games resembling images (Transformer came after, in 2017, and ViT only in 2020). In fact, CNN are still very common in modern deep RL for environment that can make use of vision like games or robotics, with existing foundation models, as they are efficient and often enough for simple environments.

Transformer-Based architecture has long been avoided in chess compared to other domains like NLP. One of the main reason was the difficulty to learn the key board features while being more computationally heavy @5. As shown in @5 and also in the new architectures proposed in @4, feature/architecture engineering tailored to learning with AlphaZero is still an important challenge. Some of the ameliorations to the ViT architecture proposed by the Leela team are described in a blogpost.

Getting the ModelThe experiments in @1 are conducted on a Transformer-based architecture, precisely the one tagged as

T82-768x15x24h-swa-5230000(weights768x15x24h-t82-swa-5230000.pb.gz). As the best nets page is regularly updated one can look in their public storage and use a related network, e.g.,768x15x24h-t82-swa-5264000.pb.gz.

# Cracking Open the Black Box

Attention Patterns

In a Transformer model it is often possible to draw some explanations by simply looking at the attention patterns without much intervention. While some patterns can be hard to construe (for a human), it’s a good metric for information movement. The “QK” circuit select the information to be moved while the “OV” circuit compute the information, see @9 for how to think about attention heads in term of circuits. Equation $\ref{eq:attention_head}$ outlines these two circuits for each head $i$.

\[\begin{equation} \label{eq:attention_head} {\rm Head}_i(x)={\rm softmax}(x^TW_{Qi}^TW_{Ki}x)\cdot W_{Oi}W_{Vi}x \end{equation}\]Attention heads in the lc0 network reveal how the model connects different board squares. It is thus natural to see a lot of attention head exhibiting patterns related to specific piece moves (pawn/bishop/knight…). For example, if a square computes something about a bishop (attack, protection, sacrifice, etc.), this computation might be relevant to other squares reachable moving bishop-like.

LimitationsInterpreting attention patterns can be limited in term of conclusion, as pointed in @10. You should keep in mind that when you interpret the attention weights (from the softmax/”QK” circuit), you only look at the selection process and can’t say anything by the actual selected computation.

Probing Analysis

Probing involves training smaller models, often linear, to extract information from a model’s activations @11. For instance, a simple probe trained on a lc0 network can show the emergence of the attack concepts, e.g., “check”, during training or layers, as DeepMind did in @12. With respect to planning, @1 showed that it was possible to predict future optimal moves, showing that such network somehow encodes future lines of play.

In order to improve the accuracy it could be tempting to augment the probe complexity, to allegedly capture the underlying representation. Yet this might lead the probe to learn other correlations, coming from the data rather than the inner model’s representation. For this reason it is always a good idea to have control tasks @7, or a control model, e.g., randomly initialised like in @1, known as the model parameter randomisation test @8.

Activation Patching

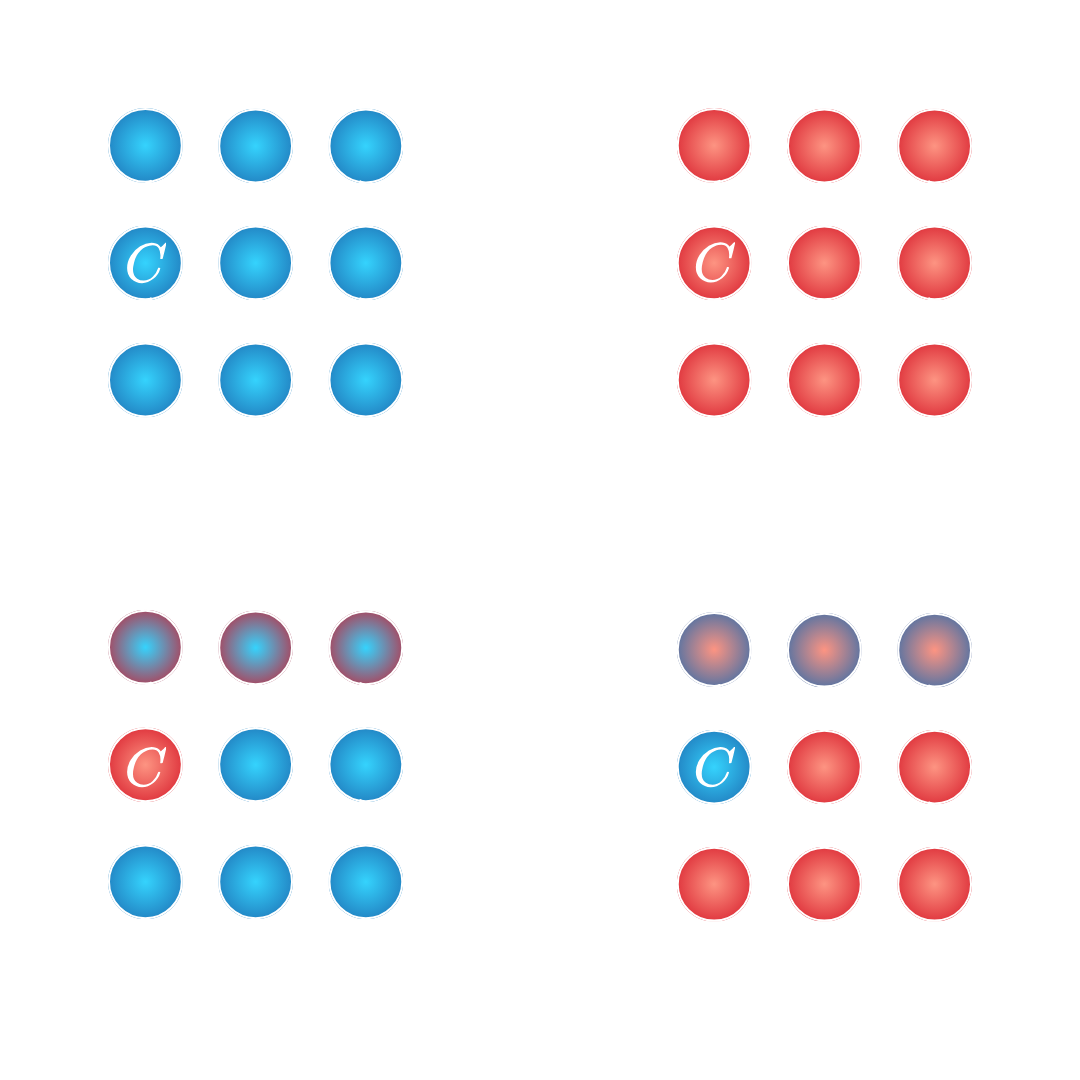

Activation patching was proposed a causal mediation analysis in order to causally measure the impact of different model’s components to downstream tasks @6. The downstream task can be a single prediction, multiple predictions or other forms of loss. Figure 1 present the different mediation analyses, using an indirect or direct intervention. For the indirect intervention (c) on a component $C$, an observed variation in a downstream metric, similar to the corrupted pass (b), implies that $C$ was necessary for the compute. While for the direct intervention (d) on a component $C$, a recovered performance on a downstream metric, similar to the clean pass (a), implies that $C$ held sufficient information.

Figure 1: Illustration of the activation patching method. This method needs two forward passes, one clean (a) and one corrupted (b). Then to measure the impact of a component $C$ on a downstream task we can use an indirect intervention (c) or a direct intervention (d).

Figure 1: Illustration of the activation patching method. This method needs two forward passes, one clean (a) and one corrupted (b). Then to measure the impact of a component $C$ on a downstream task we can use an indirect intervention (c) or a direct intervention (d).

Applying this method to lc0 networks lets us test which parts of the activations/heads/layers encode or compute critical information. By swapping activations between clean and corrupted board states, @1 pinpointed the squares that store crucial information. This information is somehow used in a planning mechanism coined “look-ahead”, which technically predicts a line of moves, taking into account the opponent’s best response.

Still FuzzyThe key details behind this “look-ahead” mechanism is still fuzzy. It is unclear to what extent the model only considered a single line of play or if/how other possibilities were rule-out. That would be a good avenue for future work.

# Exploration With lczerolens

Results Reproduction

If you want to understand the dataset generation process read appendices D & E of the original article @1. They used selection criteria based on weaker instances of the studied model and automatically generated corrupted states, pretty canny!

Using the lczerolens library, you can replicate key experiments like activation patching and probing. The library provides tools for extracting activations, visualizing attention, and conducting causal tests, now based on nnsight (an older version was based on PyTorch hooks).

Attention Patterns

Empty for now

Probing Analysis

Empty for now

Activation Patching

Empty for now

Analysing Other Models

Empty for now

What’s Next?

Empty for now

# Resources

Sources to reproduce the results:

In order to understand better the AlphaZero algorithm:

- Stanford blog post

- One of my previous blog post

- The original article of AlphaZero

- The video by DeepMind

In order to understand better how the MCTS is used in Leela:

- The original article of AlphaZero

- The blog of Leela

Other related interpretability paper on chess:

- Two papers by the interpretability team of deepmind

- Another paper on a “minichess” model

- My preliminary work using sparse autoencoders

References

- Jenner, Erik, et al. “Evidence of Learned Look-Ahead in a Chess-Playing Neural Network.” 2024.

- Pascutto, Gian-Carlo et al. Leela chess zero, 2019. URL http://lczero.org/.

- Silver, David et al. “A general reinforcement learning algorithm that masters chess, shogi, and Go through self-play.” Science 362 (2018): 1140 - 1144.

- Monroe, Daniel and The Leela Chess Zero Team. “Mastering Chess with a Transformer Model.” ArXiv abs/2409.12272 (2024).

- Czech, Johannes et al. “Representation Matters for Mastering Chess: Improved Feature Representation in AlphaZero Outperforms Switching to Transformers.” European Conference on Artificial Intelligence (2023).

- Vig, Jesse et al. “Investigating Gender Bias in Language Models Using Causal Mediation Analysis.” Neural Information Processing Systems (2020).

- Hewitt, John and Percy Liang. “Designing and Interpreting Probes with Control Tasks.” ArXiv abs/1909.03368 (2019): n. pag.

- Adebayo, Julius et al. “Sanity Checks for Saliency Maps.” Neural Information Processing Systems (2018).

- Elhage, et al., “A Mathematical Framework for Transformer Circuits”, Transformer Circuits Thread, 2021.

- Jain, Sarthak and Byron C. Wallace. “Attention is not Explanation.” North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics (2019).

- Alain, Guillaume and Yoshua Bengio. “Understanding intermediate layers using linear classifier probes.” ArXiv abs/1610.01644 (2016).

- McGrath, Thomas et al. “Acquisition of chess knowledge in AlphaZero.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 119 (2021).